By Brandie Piper

Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, is distantly related to U.S. President George Washington, explorer Meriwether Lewis, and General George S. Patton. Actor Alec Baldwin’s ancestors came to America on the Mayflower. Many famous ancestors of celebrities are well-documented, but have you ever thought about the ancestors of some of the world’s most popular food?

Throughout history, modern produce evolved through traditional plant breeding techniques. And most modern produce evolved so much that its origins are nearly indistinguishable from what it looks like today.

In honor of Ancestor Appreciation Day Sept. 27, here’s a look at some of the ancestors of modern produce and how plant breeding has transformed fruits and vegetables.

Watermelon

According to the National Watermelon Board, the first recorded harvest of the fruit was 5,000 years ago in Egypt. When those first watermelons were harvested, they were a fraction of the size they are now, measuring around two inches in diameter. The watermelons were also bitter, tasting nothing like the sweet fruit we now devour during the summer months. Traditional breeding was used to continually transform watermelon over the last several thousand years into larger, more desirable fruit.

By the mid-1600s, watermelon started to get much larger, more like the fruit we know today. But the flesh inside was downright bizarre by today’s standards. Immortalized in a painting by 17th century artist Giovanni Stanchi, sliced-open watermelons show spirals of seeds in light red flesh.

The watermelon evolved again in the 20th century when seeds started to be bred out of some varieties, a trait often misinterpreted as being genetically modified. Now, watermelons come in many shapes and sizes, colors, and tastes.

Musa acuminate: Banana’s forefather

The banana is an easy snack, often packed in school and work lunches. According to Smithsonianmag.com, the smooth, bright yellow fruit we eat today has a thin ancestor that produced pods similar to okra pods, and it was called Musa acuminata.

About 6,500 years ago Musa acuminate was cross-bred with Musa balbisiana and produced plantains, another relative of modern bananas. Plantains look similar to bananas, but they do not taste the same. They have less sugar and are starchier, and they are typically cooked before they are served in Latin American countries.

Teosinte

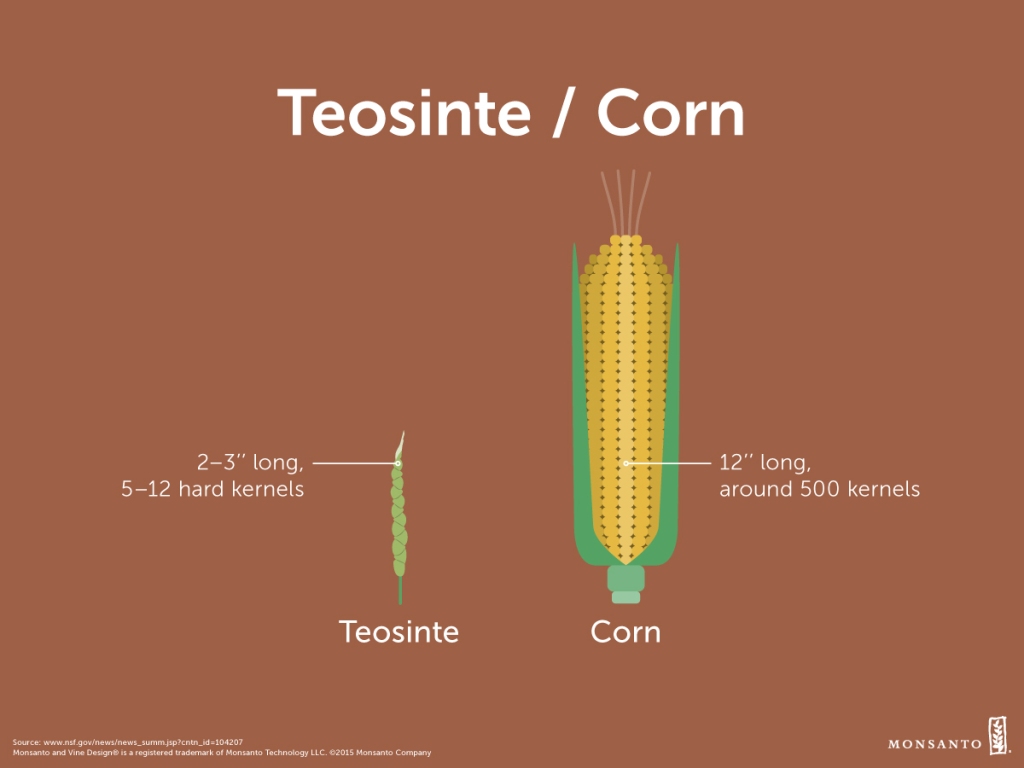

Also known as maize, modern-day corn goes back about 10,000 years, the Genetic Science Learning Center at the University of Utah reports. Its ancestor, called teosinte, was a grass that looks very different from today’s maize plant. It produced small, thin “cobs,” that were two or three inches long and contained five to 12 hard kernels.

Humans used traditional breeding techniques to breed the most desirable traits from each generation of teosinte to create today’s 12-inch ears of field and sweet corn. Teosinte’s hard kernels were difficult for humans to chew, so the firmness was bred out of the plant. Today, more than 500 easily-chewable kernels adorn each ear of sweet corn.

Carrots

According to the World Carrot Museum, carrots were originally cultivated in and around Afghanistan and were not the familiar orange color we associate with the vegetable today.

Carrots were originally yellow and purple and bred to be white and orange in the 1600s, and then red in the 1700s. Purple carrots are still grown in Europe and Asia, and red carrots can still be found in China and India.

Brassica

What do kale, cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts have in common? They can be considered cousins, because they share a common ancestor – a green, leafy plant called brassica.

As far back as 10,000 years ago, different traits in the plant were targeted by humans, leading to the breeding of many vegetables we’re familiar with today, including Beneforté® broccoli.

Beneforté® was developed after scientists went out in search of uncultivated varieties of broccoli that could produce higher levels of phytonutrients. What they found was a wild broccoli variety that had an ability to naturally produce broccoli that, on a per-serving basis, contains two to three times the phytonutrient glucoraphanin as a serving of other leading commercial broccoli varieties produced under similar growing conditions. Scientists bred this wild broccoli with traditional broccoli to produce one of Beneforté® parents. The broccoli was bred over several years to produce Beneforté®, which tastes just like traditional broccoli.

Seed bank

There are more than 1,000 banks throughout the world, which contain seeds for common crops. But there’s one place in the world that serves as an international backup, containing seeds from more than 4,000 plant species and built to withstand earthquakes, direct nuclear strikes, and climate change.

Not far from the North Pole, Svalbard Global Seed Vault was built by the Norwegian government to make sure modern varieties of fruits and vegetables do not go extinct like some of their ancestors, and to ensure seed availability in the event of a catastrophic agriculture event.

The seed vault currently holds seeds for tens of thousands of common varieties of crops and can store up to 4.5 million seed samples. Experts believe the seeds can last up to 1,000 years in the -18 degrees Celsius environment. When the vault opened in 2008 an official involved with the project told CBS News that if electricity goes out, permafrost surrounding the structure can keep it cool enough to continue preserving the seeds for about 200 years.

A long time coming

Traditional plant breeding took thousands of years and was largely based on trial-and-error. Farmers noticed certain desirable traits in the plants they grew, such as height or fruit quality, and to replicate those desirable traits in the next generation of plants, they had to breed plants with each other with the hope of producing offspring that also had the desirable traits. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. It amounted to guesswork, as the process to find out if it worked took years, and sometimes decades.

“It’s certainly a lot easier than it used to be. And now, after thousands of years, we have hundreds of thousands of varieties of crops, allowing breeders to tap into the desirable characteristics of a those plants to deliver what the farmer needs,” said Jennifer Green with Monsanto’s vegetable seed business.

The plant breeding efforts are more precise, allowing breeders to select the plants with the desirable traits and expect more predictable results. Monsanto’s vegetable seed business invests about half of its research budget on plant breeding, which includes looking for improved plant varieties in 18 fruit and vegetable crops.

“Our team of Monsanto breeders tests and develops plant varieties that can help a farmer have a successful harvest,” said Green. “Monsanto breeders connect with farmers to learn what they’re looking for when growing a crop and then go to work to find the best plants that can help. A farmer’s field may have been infected by a disease and needs a plant variety that has good tolerance to that disease. The breeder will then work to develop a tolerant or resistant variety in order to deliver it to the farmer.”

Today, plant breeding is a science, taught at major agricultural schools around the world. These breeders work for companies, like Monsanto, that then collaborate with farmers to learn about what characteristics the farmers are looking for in their crops.